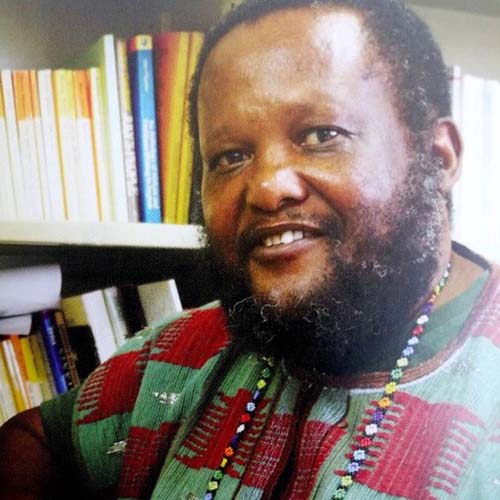

Tribute to Professor Bhekizizwe Peterson (1961-2021)

The Screen Worlds team wishes to pay our deepest respects to the great South African filmmaker and scholar Professor Bhekizizwe Peterson, who very sadly passed away in June. Professor Peterson wrote the screenplay for Fools (1997, dir. Ramadan Suleman), which was the first feature fiction film to be made by Black filmmakers in post-1994 South Africa. An adaptation of Njabulo Ndebele’s 1983 novella of the same name, the film follows Ndebele’s lead by rejecting “spectacular” modes of representation in favour of a clear-eyed focus on the ordinary. It embraces African languages and a rich jazz score composed by Chikapa Ray Phiri, and foregrounds the experiences of African women in particular.

Professor Peterson also wrote the screenplay for Zulu Love Letter (2004, dir. Ramadan Suleman), a profound and deeply moving feature fiction film about “two mothers in search of their daughters”, against the backdrop of South Africa’s Truth and Reconciliation Commission (Peterson, “Screenwriter’s Statement”, Zulu Love Letter: A Screenplay, Johannesburg: Wits University Press, p.21). There is Thandeka Khumalo, a journalist and anti-apartheid activist whose parents had to raise her daughter Simangaliso, who is deaf and mute because of violence Thandeka suffered in prison when she was pregnant. And there is Me’Tau, who comes to Thandeka to help her find the body of her daughter Dineo, a young activist who Thandeka witnessed being murdered by the apartheid police. Like Fools, the aesthetics of Zulu Love Letter are deeply influenced by musical rhythms, with the latter film embracing “interludes” in its structure.

Both films are rich ensemble works that focus on whole communities and how individuals relate to one another within those communities. Both films are also deeply relevant to contemporary South African and global society – and, in many ways, anticipated contemporary decolonisation movements such as RhodesMustFall – because of their sustained attention to how the violence of the past continues to haunt and manifest itself in the present. This can best be expressed in Professor Peterson’s own words, from his “Screenwriter’s Statement” for Zulu Love Letter:

“What fascinated me was how to capture and challenge – on the level of theme, character and structure – the assumptions made about time and experience, forms of personal and social change, healing and redemption. The political changes [in South Africa after 1994] were often glossed over as a ‘miracle’ and there was a feeling that ‘in the fullness of time’ things would resolve themselves and life would get better. The problem is that no one seemed to know the duration or content of a ‘transition’ … I was intrigued by what I suspected would be a much longer and more complicated historical and political condition than the idea of ‘transition’ allowed for. I sensed a phase that is analogous to Antonio Gramsci’s ‘crisis of authority’ or ‘interregnum’, where ‘the crisis consists precisely in the fact that the old is dying and the new cannot be born; in this interregnum a great variety of morbid symptoms appear.’ The challenge, then, was how to capture in the theme and form of the film the sense of uncertainty, of the myriad tensions between past, present and future. I do not know whether we resolved this challenge successfully but we were clear that the narrative needed to explore concerns that were in danger of being ignored, repressed or glossed over because they went against the grain of the ‘feel-good’ mantras of the new dispensation. Not to do so was to abdicate the role of the arts in speaking the unsaid or unspeakable.”

(Peterson, “Screenwriter’s Statement”, Zulu Love Letter: A Screenplay, Johannesburg: Wits University Press, p. 19-20)

In its commitment to trying to contribute in a small way to the decolonisation of film and screen studies, the Screen Worlds project sees Professor Peterson’s work as a guide and inspiration. We also see Professor Peterson himself as a role model – an artist, activist and educator who worked communally rather than individually, and who was immensely generous and kind. We encourage everyone to keep his vital legacy alive by seeking out, watching, screening, reading about, and discussing his films – not only Fools and Zulu Love Letter, but also the many important feature documentary films to which he also contributed (such as Zwelidumile and Miners Shot Down).

Like Sol Plaatje, Professor Peterson believed in “art in and for itself – as a key constituent of what makes us human” and that “the ideal education is one based on the practice and celebration of a people’s material culture, arts and heritage: ‘this kind of education embodies botho [respect, harmony, interconnectedness], humaneness, knowledge and cultural identity'” (Peterson, “Modernist at Large: The Aesthetics of Native Life in South Africa, in Sol Plaatje’s ‘Native Life in South Africa, eds Remmington, Willan and Peterson, Johannesburg: Wits University Press, 2016, p.33 and p.20).

We will always remember you and continue to learn from you, Professor Peterson.