Against All Odds: Bringing Multi-faceted China-Africa Stories to the Screen

In Conversation with Chinese Documentarian Yong Zhang (English version)

Xiaoning Lu: Since 2018, you have made several documentaries about China-Africa relations, including Africans in Yiwu, TAZARA: A Journey without an End, and Bobby’s Factory. At the moment, you are a very well-known Chinese filmmaker documenting China-Africa cultural exchanges and experiences. I wonder what motivated you to choose this particular path of filmmaking.

Yong Zhang: This can be traced back to 2012, when I started my PhD study at the Beijing Film Academy. I have always had an interest in cultural geography. However, I noticed that in the geography of cinema, Africa had yet to receive attention from Chinese film scholars. I couldn’t find any Chinese scholars’ monographs or dissertations on African cinema at that time. I had so many questions: Where can we locate African cinema? What are the distinct styles and characteristics of African films? These questions propelled me into a journey of exploring Africa.

Before I set foot on the African continent in 2015, I had learnt about Africa from various sources, which associated this continent with vocabularies such as blood, violence, poverty, and AIDS. One primary source of my knowledge about Africa was Hollywood blockbusters, such as Blood Diamond (2008), Hotel Rwanda (2004), and Black Hawk Down (2001). After arriving in Africa, I realised that this continent had been demonised through stereotypical representations, and I began to ask myself what I, as a filmmaker, could do about it.

Ever since I started my fieldwork in Africa, I have had continuing opportunities to observe “real” life in Africa and to learn about more stories related to Chinese people in Africa and Africans in China. Later, I started to explore how to build a bridge of communication and understanding between the Chinese and the Africans through creative works. For this task, the documentary is the best medium, and that’s how I started making documentaries about China-Africa relations.

Lu: Besides being a filmmaker, you are a film scholar. I read your 2018 article “Africa on the Chinese Screen: Problems and Reflections” with much interest. This article discusses four recent Chinese feature films set in Africa, including the immensely popular Wolf Warrior II. I am intrigued by your observations that these films somehow reinforce Hollywood’s stereotypical depiction of Africa. As we know, China has developed extensive engagement with Africa in the past two decades. However, when telling stories about Africa onscreen, Chinese feature film directors have chosen to follow Hollywood narrative conventions rather than drawing on their direct observations of African realities. How have these directors found themselves in this situation?

Zhang: There are many contributing factors. The first is related to Africa-themed movies produced by Hollywood. These movies have greatly influenced ordinary Chinese audiences’ perception of Africa and directly influenced Chinese filmmakers. When the latter started their Africa-themed projects, they unconsciously imitated some Hollywood blockbusters. Anyone familiar with Hollywood films can quickly discover the close connection between Wolf Warrior II and Hollywood productions, including Black Hawk Down (2001), Tears of the Sun (2003), Hotel Rwanda (2004), and Blood Diamond (2008). At the narrative level, Wolf Warrior II synthesises many of the elements common to those Hollywood blockbusters, such as violence, ethnic conflicts, hunger, poverty, and disease. There are also a few scenes of wild animals on the African savannahs rather awkwardly inserted into the film narrative. It is no exaggeration that you can find all kinds of conventional Western imaginations of Africa in this Chinese movie. Since Wolf Warrior II uses Hollywood and Hong Kong action and visual effects experts and expensive military props, it creates an even grander blood-and-gore spectacle than Hollywood productions. The film has become a Chinese version of an Africa-themed Hollywood movie, blurring the boundaries between Chinese blockbusters and Hollywood films.

The second factor has to do with the film market. China’s domestic market is the primary driver for Africa-themed Chinese movies. Due to its narrative defects, it is not surprising that Wolf Warrior II only managed to get RMB 10 million at the overseas box office. This performance contrasts with its exorbitant gain of RMB 5 billion at the Chinese box office. As for the producers, if they can tap China’s massive domestic film market and rely on domestic audiences’ growing consumption power, their investment is bound to yield a profitable return. Therefore, they would rather pay more attention to China’s small towns or tier 4 market than the overseas film market. Although Wolf Warrior II has been exhibited outside China, overseas audiences are not its target market. Here are the paradoxes: while Chinese filmmakers wish to introduce their films on the global stage, they take the domestic market as their primary concern. While they want to focus on Africa, they do not have the necessary attitude to film Africa seriously and only want to use African subjects as a selling point.

The third factor is fundamental: neither Chinese filmmakers nor Chinese audiences understand Africa sufficiently. Africa-focused Chinese films have not caught up with the social development in African countries. In the meantime, limited by their knowledge, ordinary Chinese have particular expectations of Africa-focused films. These inevitably result in a chasm between China’s grand narrative about nationalism and its cinematic depiction of Africa. Suppose there is a conventional Chinese comedy or romance film revolving around ordinary African people. It will probably not be popular among Chinese audiences because it differs from the familiar image of Africa that has been deeply ingrained in the collective imagination. The current state of Africa-themed Chinese films reveals the importance of having arts and humanities exchanges while building Sino-Africa economic cooperation. Whether an African-themed movie with a distinctly Chinese style or a Sino-African coproduction, a good film is predicated upon Chinese people’s better understanding of Africa.

Lu: Since your directorial debut, Africans in Yiwu, you seem to take a particular interest in documenting ‘intercultural’ aspects of China-Africa relations. Why do you prefer making documentary films? What is the most challenging part of making documentaries about China-Africa relations?

Zhang: In my mind, documentary film is the best medium to promote mutual understanding between Chinese and African peoples. By following my documentary subjects and constant observation, I gain a more direct and deeper understanding of African societies and Sino-Africa exchanges. Making documentaries also allows me to bring multi-faceted Africa to audiences. In addition, it is more costly to make feature films than documentaries in China. Feature film directors must consider market returns. Since making documentaries requires less financial investment, I can afford the financial risk if my documentaries do not have a good market return.

What I found most challenging in making documentaries on China-Africa relations is the lack of an appreciative audience. I must remain an idealist to carry on with what I am doing. Many Chinese audiences are interested in topics such as wild animals in Africa. There are many such short videos on Chinese TikTok and Kuaishou. Some documentaries which capitalise on African exoticism, including the negative aspects of African societies, have also attracted hits. Since my documentaries are primarily about social and cultural aspects of China-Africa relations, they appear a bit odd in this group of Chinese films.

Lu: Your films Africans in Yiwu, Chinese Meet Africa, TAZARA: A Journey without an End and Bobby’s Factory all deal with Sino-African interactions. What is your specific take on each of those documentaries? Did you pick particular themes?

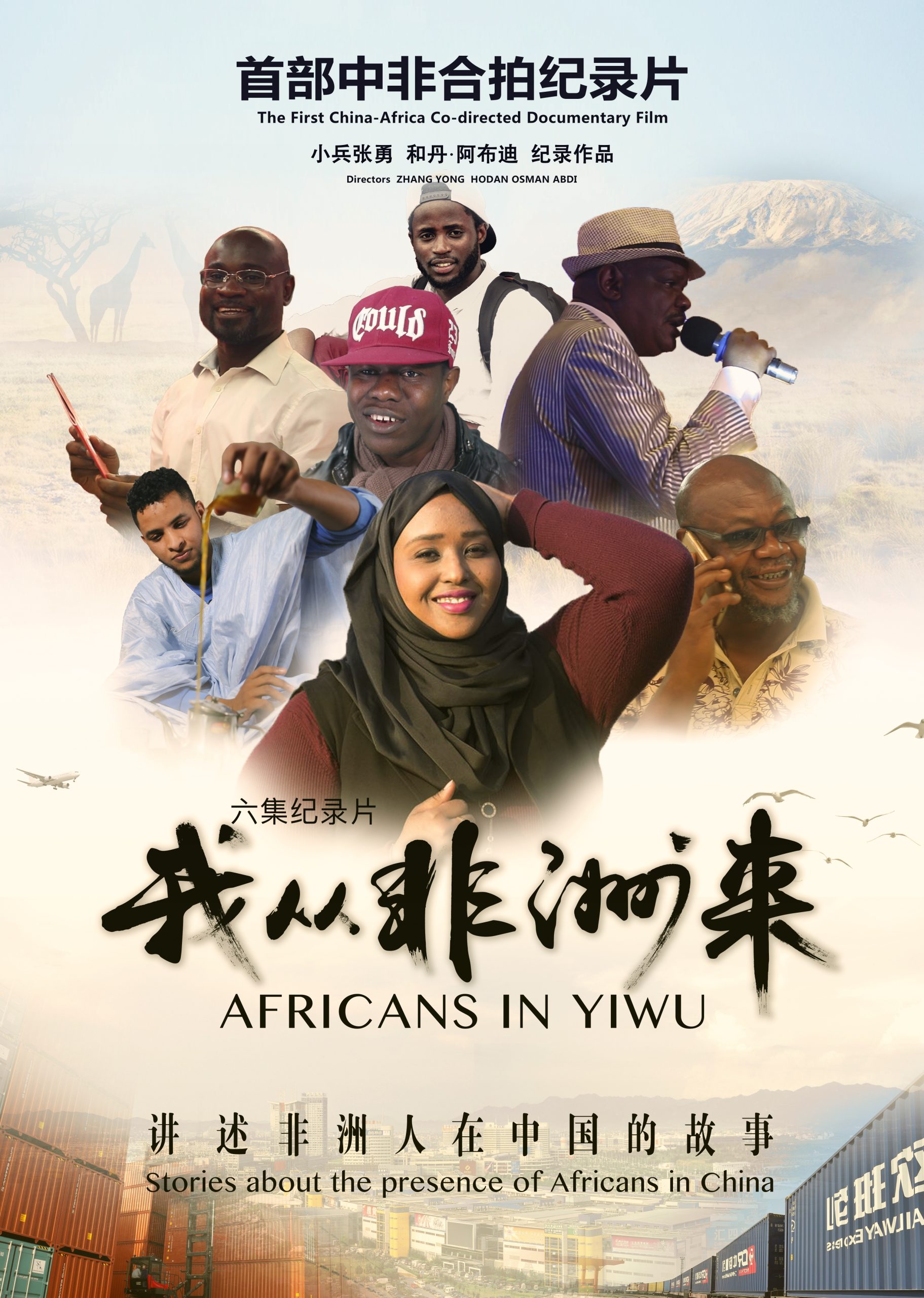

Zhang: Africans in Yiwu depict many aspects of the lives of Africans in China, including their business and charity activities, their marriages, their education, their predilection for gourmet food, and their involvement in arts. The film aims to dismantle the stereotypes of Africans by telling uplifting stories of these industrious and entrepreneurial individuals. In terms of narrative style, we emphasise showing “Africans telling their stories in their voices”.

As a sequel to Africans in Yiwu, Chinese Meet Africa keeps the same narrative style but tells the other side of the China-Africa story. The film selects representative examples from over 1 million Chinese in Africa. It tells various stories of hardworking and enterprising overseas Chinese who help connect China with Africa. My original intention in making these two documentaries is to follow the well-established international narrative convention of telling the small stories of ordinary people. I hope to tell the individual stories of “Africans in China” and “Chinese in Africa” well so that audiences receive them well at home and abroad. This way, we can hopefully break the Western monopoly of public opinion on China-Africa issues.

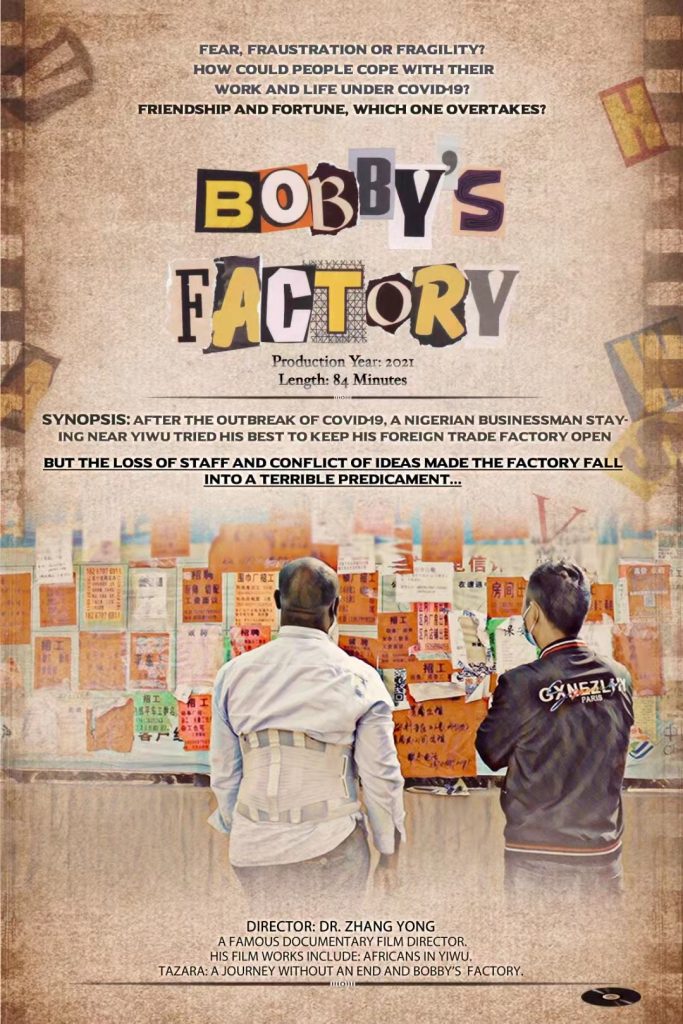

The central characters of Bobby’s Factory first appeared in my documentary Africans in Yiwu. Because of my first documentary film, I developed a friendship with Bobby and his Chinese wife, and they appreciated my creative work. In 2017, Bobby changed his profession from being a chef to running a cosmetic factory targeting the Western African market. I realised that this is an exciting change. As far as I know, most African business people in China are intermediaries, and Bobby is the first African who opens a factory in China. Therefore I decided to continue to film him. After filming him for a year, the Covid pandemic suddenly broke out. The foreign trade factories encountered unprecedented challenges, and Bobby’s factory was no exception. His story then became my first feature-length documentary.

As for TAZARA: A Journey without an End, it is very different from my other films with regards to thematic focus. Although I had been making documentaries on China-Africa relations, I was used to creating micro-narratives. Initially, I felt tremendous pressure when dealing with this grand historical subject as TAZARA is China’s first major foreign aid project. Later, I made two field trips and found some residents, tourists and Chinese experts along the railway. Unlike other Chinese documentaries on TAZARA, my film adopts a micro perspective. It tells stories of the ordinary people along the TAZARA, thereby constructing a grand historical narrative of China-Africa relations.

Lu: The West remains the third party, even for Chinese documentary filmmakers. TAZARA: A Journey without an End is a good example, as you made this film to directly respond to the British documentary African Railway by journalist Sean Langan. Western filmmakers’ representations of Africa are undoubtedly conditioned by individual directors’ knowledge of Africa and the prevailing ideology in the West. In China, “Sino-African friendship” has been the dominant discourse promoted by the Chinese government to characterise China-Africa relations since the mid-20th century. In recent years China made a massive investment in Africa. Although the Chinese government suggests the current China-Africa cooperation as a win-win South-South partnership, such discourse does not seem convincing to many people in the West. We often see that China is depicted as a ‘neo-coloniser’ in Western mass media. As a documentary filmmaker, how do you position yourself in this context?

Zhang: Indeed, in recent years, some Western media spearheaded by BBC made quite a few documentaries criticising China’s investment in Africa, for example, The Chinese Are Coming and African Railway. These documentaries tend to generalise some problems to foreground the negative image of China in Africa. Not only do Chinese audiences dislike such portrayals, but African audiences do not subscribe to that kind of viewpoint. The Chinese state media are on the other end of the spectrum. They are keen to produce grand narratives about China-Africa relations. They emphasise China’s aid to Africa but never touch upon the profits and benefits China has gained in those cooperations. As you said, those narratives do not hold persuasive power for international audiences.

In my filmmaking, I like to pay close attention to the diversity and complexity of China-Africa collaboration. Such cooperation is not one-dimensional, and I believe we should hold a cautious attitude or even resist any attempts that simplify matters into stereotypes. We can’t use black or white to characterise a person or a place, and this holds for African and Sino-African cooperation. When making documentaries, including Africans in Yiwu and Chinese Meet Africa, my team and I have used the “multiple themes, multiple characters, and multiple episodes” strategy. This strategy ensures we have a wide range of representations of China-Africa relations.

Moreover, we usually spend an extended period with our documentary subjects, and this is to avoid exoticising their stories from a voyeuristic perspective. Take my film Bobby’s Factory, for example. Compared to other Chinese or Western filmmakers who film African factories in China, my team and I have invested far more time in building a relationship with our documentary subjects and following up with them. Consequently, our film has a richer representation of Africans in China. For instance, this film, on the one hand, represents Bobby’s African identity and how he blends into the community made up of his Chinese employees; on the other, it tells a universal story. Bobby has been living in China for over ten years. During this period, he got married and had a child. He is a “China expert”. During the Covid pandemic he faced the same challenges that many Chinese bosses of similarly-sized foreign trade factories experienced. These were context-specific problems and had nothing to do with skin colour. Tencent video, a famous Chinese video streaming website, praises this documentary’s value in anthropological and sociological studies because we document, observe and present Bobby’s life as an element of the Chinese economic world.

Lu: It seems to me that your particular way of telling African stories involves decolonising screen culture at many different levels. Do you consciously develop a specific style in your documentaries to counter the visual language in relevant Western documentaries about China-Africa relations?

Zhang: I wouldn’t say that visual language in documentaries is complicated. I often remind my cameraman to avoid using high-angle or low-angle shots to film African subjects on the film set. Instead, we use eye-level shots to guide our audiences to view the Africans as their equals. At the narrative level, my documentaries such as TAZARA: A Journey Without An End, Bobby’s Factory and Chinese Meet Africa all focus on “small characters”. Even when documenting the mega infrastructure project of TAZARA, we did not interview many political leaders or high-ranking officials. We put much focus on ordinary Africans along the railway line. I prefer letting ordinary people or the subaltern tell their own stories, and I wish my films have a flavour of humanity and everydayness. In addition, we rarely use voice-over narration, as we do not want to speak on behalf of our characters.

Lu: Would you like to share with us what project you are working on now?

Zhang: I am working on the documentary Generation Z’s China-Africa Stories. Each instalment pairs one Chinese with one African person born after the 1990s and narrates stories arising from their interactions. I have been to Africa about ten times. What has struck me most is Generation Z. They exhibit surprising maturity when communicating with their counterparts. Compared to the older generation, they have access to more information and are more open-minded and less prejudiced. This documentary focuses on Generation Z in order to demonstrate the continuity of China-Africa cooperation: there are people in every generation who build cultural bridges. The baton has been passed onto the generation born after the 1990s and will continue to be passed onto young people born after 2000 or 2010. I believe the young generation is our future, and their thoughts and ideas will shape the future of China-Africa relations. I would love to document their stories.

YONG ZHANG’S FILMS

Africans in Yiwu我从非洲来 (2017) https://www.iqiyi.com/a_19rrhcmp05.html?vfm=swwwds56

It is also available on YouTube.

Episode 1: https://youtu.be/YfU_M_x8_Fc

Episode 2: https://youtu.be/w1SVQSF0PCo

Episode 3: https://youtu.be/IWwShq_8s58

Episode 4: https://youtu.be/UUjKNIWoZew

Episode 5: https://youtu.be/2HTKL4AYK7w

Episode 6: https://youtu.be/usm4cWJWBZE

TAZARA: A Journey without an End 重走坦赞铁路 (2018)

https://www.iqiyi.com/a_19rrhyfbud.html

Bobby’s Factory (aka China-Africa Factory)波比的工厂 (2021)

https://v.qq.com/x/cover/mzc00200zurg1bq/u00446xbck4.html

SOAS Library collection MDVD24 /9798 MDVD24 /9799

Chinese Meet Africa 我到非洲去 (2022)

https://v.qq.com/x/cover/mzc00200jefo9ji/b0044yk0g29.html

迎难而上:将多元的中非故事搬上银幕

—与中国纪录片导演张勇的对话

陆小宁:自2018年以来您已经拍摄了好几部有关中非关系的纪录片,比如《我从非洲来》,《重走坦赞铁路》,《波比的工厂》以及《我到非洲去》,也已经成为最受瞩目的拍摄中非交流题材的中国导演。请问是什么触动了您走上这条电影道路?

张勇:2012 年左右,我开始在北京电影学院读博。平时自己一直对文化地理学感兴趣,在当时的电影文化版图中,非洲还是尚未被中国电影学术界关注的一片大陆,我那个时候没有看到一篇系统的由中国人写作的一部有关非洲电影的书或是学位论文。于是我就在想:非洲电影在哪里?非洲本土电影的风格和特点又是什么?带着这些疑问,我迈出了走向非洲的第一步。

在我2015年亲身站在非洲土地之前,我所接受到的有关信息往往将非洲与血腥、暴力、贫穷、艾滋病等词汇联系在一起,而这些的来源主要是好莱坞电影《血钻》、《卢旺达饭店》,《黑鹰坠落》、等所谓的大片带给我们的。来到非洲之后,我意识到这是一片相对被污名化、被影像叙事刻板化的大陆,我在想我作为电影人能做什么?通过陆陆续续地实地调研,我看到了非洲更多的现实,了解到更多的中国人在非洲的故事,以及非洲人在中国的故事。后来我就开始探索通过创作的方式,搭建起一座沟通和理解的桥梁,让更多中国人了解非洲、也让更多非洲人了解中国,而纪录片是在这方面最好的媒介,就这样走上了中非主题纪录片创作这条路。

陆: 您不仅是一位导演而且是一位学者。在您2018年写的《中国银幕上的非洲:问题与反思》一文中,您提到了四部以非洲为背景的中国国产故事片,包括我们耳熟能详的《战狼2》,并有一个很有意思的观察:您指出这些电影在某种程度上加强了好莱坞电影所塑造的有关非洲的刻板印象。众所周知,在过去二十年间中非建立了广泛的联系,但中国电影人在“讲非洲故事” 这一点上更多追随了好莱坞电影叙事模式而不是从自己对非洲直接观察出发。您能否跟我们解释一下中国电影人为什么有这种处境?

张: 这里面有好几个因素。一是好莱坞非洲题材的深刻影响,它不仅深刻影响了中国普通观众对非洲的印象,更直接影响了中国的创作者,他们刚开始进入这个领域拍摄非洲题材电影时不自觉地模仿了好莱坞非洲大片,熟悉好莱坞的观众不难发现,《战狼2》是《黑鹰坠落》(Black Hawk Down,2001)、《太阳之泪》(Tears of the Sun,2003)、《卢旺达饭店》(Hotel Rwanda,2004)、《血钻》(Blood Diamond,2008)等等好莱坞非洲题材的集大成者,它在叙事上集结了好莱坞多年走进非洲的所有经验:暴力、种族冲突、饥饿、贫困、疾病,还有几乎是硬缝入进去的几个动物和大草原风光镜头。毫不夸张地说,西方观众有关非洲的种种想象在这里无所不有。由于聘用了好莱坞和香港的动作和特效团队,以及重金购置了相关军用道具,影片有关血肉横飞和炮火硝烟的种种展程,相比好莱坞影片有过之而无不及,影片化身为一部中国版的好莱坞非洲大片,使观众仿佛忘了自己看的究竟是中国电影还是好莱坞电影。

第二点是支撑中国制作者叙述非洲的模式,核心的考量在于国内市场。由于叙事的缺陷,影片几乎不可避免地造就了国外市场仅1000余万人民币的票房成绩,这与国内市场50多亿的票房差距也构成中国电影史上的一大奇观。然而,对于片方来说,当中国电影市场体量足够大、国内消费力足够强时,把握好国内市场就足以获取高额回报,因此,与其在意海外市场,不如在意中国四线城市市场。对于《战狼2》而言,影片尽管已在海外上映,但其市场定位并不在海外,影片走进非洲(取景)其实是为了走进中国(市场)。于是,出现了一个悖论:一方面,中国电影人希望走出国门走向世界,另一方面,我们定位在国内;一方面,我们希望聚焦非洲;另一方面,我们并不严肃看待非洲并且拍摄非洲,把非洲当做卖点。

第三点,最核心的是中国无论是创作者还是观众,都对非洲的了解不足,集中体现在电影创作者的非洲叙事没有跟上非洲社会现实的发展变化,与此同时,普罗大众对非洲的接受还没到达正确认知的水准,因此不可避免地出现了国家宏大主题与非洲叙事的断裂。设想一下,如果拍一部正常表现非洲和非洲人的喜剧抑或爱情类型电影,恐怕没那么多受众要看,因为不符合他们的期待或对于非洲已有的想象?作为社会的镜子,电影叙事其实反映出中国和非洲在经贸合作过程中加强人文交流的必要性,而一部真正意义上的具有中国特色的非洲题材影片甚至是中非合拍片,有赖于中国社会对非洲的认知水平的整体提升。

陆: 自拍摄处女座《我从非洲来》以来,您好像对纪录中非关系中的“跨文化”的维度情有独钟。请问为什么对拍摄纪录片来有这样的偏爱?拍关于中非的纪录片最大的难处在什么地方?

张: 在推动中非了解和理解方面,我觉得纪录片是一个最好的媒介,我们通过不断地跟拍,不断地观察,可以对非洲人文和中非交流有更直观且深入的理解,也可以呈现非洲的多元面向;而且在中国的语境下,剧情片远比纪录片大成本高,要考虑市场回报,纪录片相对来说成本低一些,没有市场效益也能接受。

拍关于中非的纪录片最大的难处在于曲高和寡,您需要有持久的情怀来支撑。很多中国观众会喜欢有关非洲的动物等题材,国人抖音、快手上也很多类似的吸睛短视频,或者其他奇观类纪录片,如消费非洲丑陋、女性等,点击率很高,我主要拍人文题材,因此显得另类。

陆:《我到非洲去》、《我从非洲来》、《重走坦赞铁路》、《波比的工厂》同样作为中非题材,它们的选题立意和切入点等各有什么侧重?

张: 《我从非洲来》讲述非洲人在中国的经商、公益、婚姻、教育、美食、艺术活动,呈现非洲人在中国闯荡商海、勤劳创业、积极正面的故事,以破除对非洲人的刻板印象。在具体叙事风格上, 定位为“讲述非洲人自己的故事”、“发出非洲人的声音”。

《我到非洲去》作为第二季,沿袭了《我从非洲来》的叙事风格,逆向讲述中国人在非洲的故事,选取在非洲打拼、生活的100多万中国人中的典型代表,讲述他们非洲这边陌生的土地上勤劳创业、锐意进取,将个人和时代、中国和非洲紧紧地联系在一起的异乡故事。这两部纪录片创作的初心都是遵循国际流行的小人物叙事风格,希望通过讲好“在中国的非洲人”以及“在非洲的中国人”的个体小故事,让国内外媒体和观众都能接受,从而打破西方在中非问题上的舆论垄断。

《波比的工厂》中的核心人物波比其实来自于《我从非洲来》,我们拍完《我从非洲来》后和波比夫妇成为了好朋友,他们对我们的创作很认可,从2017年开始,波比由厨师转向开工厂,做化妆品销往西非,我意识到这是一个有趣的转变。在我的研究视野里面,非洲商人在中国大基本都是做中介,波比是第一个在中国开工厂的非洲人,我们决定随着继续跟拍他的故事。跟了一年多时间后,疫情来临,外贸工厂遭遇前所未有的挑战,一个由非洲人开办的工厂的沉与浮开始呈现,由此成为了我个人第一部长片作品。

在我创作的所有纪录片中,《重走坦赞铁路》是选题立意最为不同的一个。尽管我长期做中非题材纪录片,但我选取的都是微观叙事,面对坦赞铁路这一新中国第一大援外工程这样一个宏大的历史客体时,我觉得我驾驭不了这个题材,它太厚重了。直到去调研了两次后,我找到了沿线一些当地居民、游客、中国专家,我才形成了自己的叙事思路。不同于其他媒体的坦赞铁路纪录片,我们依然采取的是小人物视角,讲述这条铁路周边的小人物故事,用小人物构建大历史。

陆: 对中国的纪录片创作者,西方也还是作为第三方存在着的。这一点在您的《重走坦赞铁路》体现的最为明显,因为这部片子就是对BBC记者Sean Langan所拍的纪录片《非洲铁路》的直接回应。西方导演对非洲的刻画自然受制于他们自身对非洲的了解以及他们所在社会主导意识形态的影响,但中国政府自二十世纪中期开始宣传的‘中非友谊’ 也多少会在中国导演身上留下印记。近年来中国在非洲大力投资,尽管中国政府将现在的中非合作总结为双赢的“南南合作“,这一话语在西方世界并没有太大的说服力。尤其是西方的大众传媒经常指责中国为非洲的‘新殖民者’。 做为一个纪录片创作者,您是如何置身其中的呢?

张:以BBC为代表的西方媒体近年来确实制作了一系列纪录片来批评中国在非洲的投资,如《中国人来了》、《坦赞铁路纪行》,他们经常抓住一些问题以偏概全,突出中国在非洲的负面形象,但其实中国人不喜欢,非洲人也未必认同。而中国的官方媒体又走向了另外一个极端,追求宏大叙事,强调中国对非洲的援助和帮助,不体现中国从非洲带来的收获和利益,这就如您所说在国际上站不住脚。

我在创作过程中比较在意呈现中非合作的多元性和复杂性,它不仅仅只有一个面向,我们对任何符号化行为都保持谨慎甚至抗拒的态度,任何一个人一个地方都不是非黑即白,都不是单向度的,非洲也一样,中非合作也如此。具体而言,我和我的团队一方面采取多主题多人物的系列片模式,如《我从非洲来》《我到非洲去》,确保我们选取的人物和主题覆盖更多的范围,避免一叶障目不见泰山;另一方面,我们通过长时间的跟拍,避免以猎奇、窥视的视角去讲述,我们在《波比的工厂》等片制作过程中比同类题材的中国和西方制作团队付出的时间,跟拍的时间是多很多的,对非洲人在中国这个问题的呈现也更加丰富。在这部影片中, 我们一方面要呈现波比的非洲身份、非洲经验在这个中国员工组成的工厂里的落地和融合;另一方面,他的故事又有普遍意义。波比他已经在中国这十来年,娶妻生子等等,他完全是个“中国通”,他在疫情背景下遇到的问题,是所有同等规模的外贸工厂都遇到的困难,与其他中国老板无异,这是由环境所决定的,不是肤色的问题。中国著名视频网站腾讯评价这部片子时指出它具有人类学、社会学等研究文献价值,因为它将波比的生活作为中国经济生活里的一份子、作为一个代表去记录、观察、呈现。

陆: 看来您自己的创作过程中已经有好几个层面涉及到解构以西方为主导的视像文化。那您有没有有意识地在自己的纪录片里发展中一套镜头语言来结构相关西方纪录片的影像语言呢?

张: 纪录片的镜头语言不复杂,我在拍摄现场对摄影师的要求是尽量避免俯拍或仰拍非洲人,而更多是平视的视角,希望引领观众平等地看待非洲和非洲人;在叙事模式在我们无论在《重走坦赞铁路》还是《波比的工厂》、《我到非洲去》都遵循小人物叙述模式,面对坦赞铁路的巨大工程我们也没有采访几个政治领袖或高官,更多是沿线的人物,我喜欢让小人物、底层人物讲述自己的故事,拍出人情味和烟火气;另外,我们也很少用解说词,不想代替人物说话。

陆: 您愿不愿意分享一下最近在做什么项目?

张: 新作的话,我们在做系列片《90后的中非情缘》,每集会挑选一个中国 90 后与一个非洲 90 后作为主要人物。在我十次左右去非洲的经历中,最让我震撼的是90后,他们在中非领域表现出来的成熟是国人所未理解的, 更开放、包容,接触的信息也多,没有老一代的歧视非洲的思想。这部纪录片聚焦于这一特定的群体,去体现中非合作交流的一种延续性:每一代都有致力于搭建中非合作之桥的人,而现在这个合作的接力棒已经递交到了90后的受众,未来还会有00后,10后……我觉得青年是未来,他们的想法会影响中非关系的未来,我希望记录下他们的中非故事。