Collaborative Listening, Collaborative Pedagogy

The short essay is complemented by a special conversation between Dr Albertine Fox and filmmaker Katy Léna Ndiaye. You can access the French version here and the English version here.

Ce court essai est accompagné d’une conversation spéciale entre le Dr Albertine Fox et la cinéaste Katy Léna Ndiaye. Vous pouvez accéder à la version française ici et à la version anglaise ici.

This short essay arises from my recent experiences of designing and teaching the undergraduate module ‘Francophone Women Directors: Documentary Filmmaking’ at Bristol University, which has been running since 2018. This module asks students to examine the intersections of sexuality, race, gender, religion, and nationality through a comparative study of diverse documentaries by women directors from the Francophone world.[i] The teaching material is organised to allow uncomfortable questions to be posed about the gendered and racialised differences between the various ‘personal documentary’ subjects and styles. It gives attention to feminist and queer-themed subjects and involves close analysis of short sequences and accompanying discussions of theoretical ideas. These include arguments and concepts explored by Sirma Bilge (the depoliticisation of intersectionality), bell hooks (the margin as a site of resistance), Chandra Talpade Mohanty (the specificity of location), Trinh T. Minh-ha (‘There is no such thing as documentary’), and Teresa di Lauretis (‘Is there a feminine aesthetic?’). It also considers economic and institutional structures and the effects of decisions that contribute to racial and gender underrepresentation in the film industry, questioning which films and filmmakers are funded, supported, distributed, studied in universities, and are prioritised in critical writing rather than being overlooked or confined to the footnotes.

Gradually, I have forged collaborative relationships with some of the filmmakers whose work is included as primary material, enabling a dialogue to take place between myself as teacher, my students, and the individual artist, accompanied by a more immediate awareness of the context in which they are working. However, these relationships remain necessarily fragile, dependent on trust, a commitment on my part to slow reflective scholarship, and on the gradual fostering of reciprocity by sharing our ideas and experiences and feeding back on each other’s projects-in-progress. On a practical level, it is also essential that I follow the rhythm and pace of the artist’s creative process, respecting their filmmaking schedule, adapting to their communication preferences, and valuing the layered meanings in their silences as well as in their words. There is no such thing as quick and easy communication, or uncomplicated and depersonalised solidarity work, in this context. Moreover, to sidestep the power structures underpinning my own intellectual positioning would render my work unethical and meaningless.

The first time I ran the module, some of the students questioned the validity of their work, which enabled us to examine our own personal connection to (or disconnection from) the films and readings, to explore whether our relationship to the material was possessive and appropriative and to challenge ourselves and each other during this process. We also discussed the institutional structures within which the module is couched (who is it for?). Who are we, as a white majority of staff and students working in a competitive neoliberal university environment, to do this work on (but not with) the makers of our critical ‘objects’ of study? These unresolved conversations called for a willingness on my part to openly acknowledge when I did not have an answer or a solution, and it made me think again about the usefulness and legitimacy of such a module. I wondered if the only effective way to run it would be to co-teach it alongside the filmmakers whose work features as primary material. Another idea I am still pondering is to transform the classroom into a filmmaking workshop and the students would make short video essays in response to the documentaries they study. These student-made video essays would be the only viable critical ‘objects’ we could discuss and critique. Rather than focusing directly on a set film, which fixes it problematically as an object at a distance from us, it would enable the students to explore their particular relationship to the set film via their creative work. Lindiwe Dovey’s proposition that our pedagogy should not only be concerned with teaching others ‘about’ the horrors and injustices of the past but it should also constitute a doing, in the form of ‘an activist practice that does not simply critique, but that is capable of transforming society by imagining and inspiring new, more positive, more respectful futures’, is invaluable because it offers a quasi-cinematic vision for the classroom.[ii] The classroom could become a site that enables students and teachers alike to experiment with filmmaking as a means of thinking, listening, and acting creatively in order to disrupt, resist, and intervene in dominant discourses to bring about social change.

With a PhD on the role of sound in Jean-Luc Godard’s post-1979 films and videos, followed by my ongoing research and writing on Chantal Akerman’s filmmaking corpus, my teaching and publishing experiences have been closely linked to experimental audio-visual works by well-known and much-discussed European filmmakers. After publishing some of my doctoral work, it became very clear to me how (relatively) straightforward it was to find an audience for my ideas on Godard’s films, and thus a place for myself in the world of film criticism, which was not the case with other female artists. Writing about the films of a high-profile and provocative white male artist and ‘personage’ of European cinema (even when avoiding his most famous works), is a path well-trodden in the world of Euro-American film criticism, dominated primarily by white male critical voices. Nevertheless, I still find it engrossing and exciting to discuss Godard’s films with my students and I am constantly pushed out of my comfort zone, freed to make creative connections across and beyond disciplinary boundaries. Yet if my doctoral research on Godard’s films made me reflect on my own positionality as a female spectator and scholar, it did not make me reflect explicitly on my racial privilege as a white academic researcher. Over the past three years, the exchanges I have had with my students, and simultaneously, with Katy Léna Ndiaye, Corine Shawi, Lara Zeidan, and Nada Mezni Hafaiedh, have made me more aware, in a tangible sense, of wider political, economic, and socio-cultural factors influencing what is funded, what is made accessible to the public, where the work is shown, how the material is received by commentators, and who comments on it, which affects how it is heard and seen.

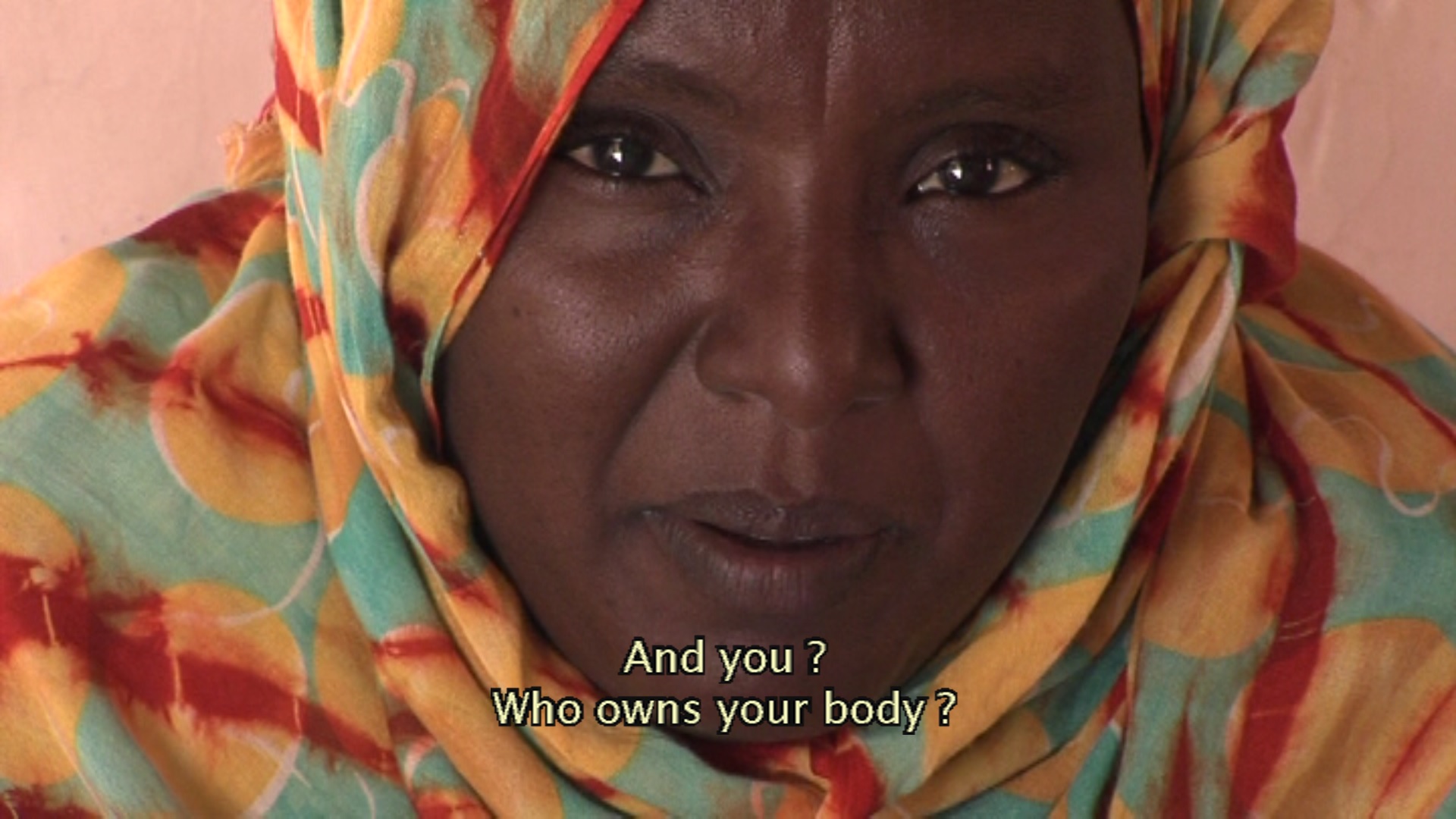

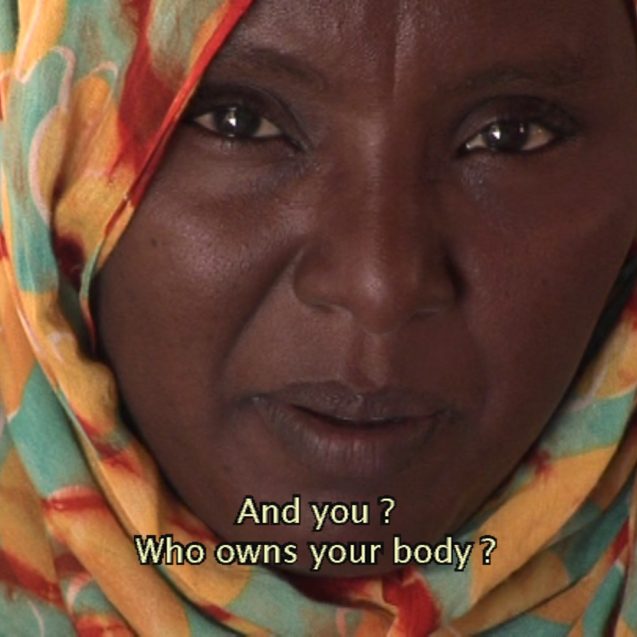

In October 2019, I attended a screening at the Festival des Libertés in Brussels of the documentary On a le temps pour nous (Time is on Our Side) by the documentary filmmaker Katy Léna Ndiaye, featuring the Burkinabe rapper, poet, and political activist Serge Bambara (aka Smockey) who participated in a fascinating post-screening Q&A alongside Ndiaye and we had a brief conversation at the end. The following year, Ndiaye generously responded to my questions about three of her documentaries to support my teaching and research, two of which are included on the teaching programme: En attendant les hommes (Waiting For Men), 2007, and Traces, empreintes de femmes (Traces, Women’s Imprints), 2003. Both films are available to purchase on DVD from Neon Rouge Productions. Waiting For Men (with English subtitles) is available online via Amazon Prime Video and Traces, Women’s Imprints can be accessed via Culture Unplugged. Additional conversations with Ndiaye have since helped me to better grasp the nuances of the ideas expressed during our exchange, while also highlighting the problematic process of translation when moving from one colonial language to another. This process of to-and-fro communication with the filmmakers whose work I explore alongside my students has helped me to reassess my own relationship to their films, to question my own assumptions and responses in a self-critical manner, as a white academic working in a School of Modern Languages at a British university, and to listen attentively to their perspective as filmmakers living and working in both European and non-European contexts.

In Ndiaye’s documentaries Traces, Women’s Imprints (hereafter Traces) and Waiting For Men the female-led tradition of wall painting features centrally. The first film concerns a community of Kassena women in the village of Tiébélé in Burkina Faso, and the second spotlights three middle-aged Muslim women from the small Mauritanian town of Oualata. The filming of this latter documentary took place when the men were about to return home. Through the words they utter, the filmed participants counter stereotypes that picture Muslim women as intrinsically oppressed by patriarchal power. In this way, the film helps to engender the form of feminist solidarity outlined by Chandra Talpade Mohanty as part of her theory of ‘feminism without borders’, which is entwined with her understanding of decolonisation and anticapitalist critique. Mohanty argues that feminist solidarity is not a homogenous, universalising, or vague form of borderless ‘sisterhood’.[iii] By contrast, it requires one to learn how to unsee ‘women as a homogeneous group or category (“the oppressed”)’ when their unity is based on gender alone, and to hear how women are in fact ‘produced’ through social relations in particular local contexts.[iv] Through the communicative practice they elicit, based on listening to the women’s words and gestures without listening over them (hearing only one’s own false projection of preconceived ideas about who they are or what they represent), Ndiaye’s films teach their audiences how to practise the kind of feminist solidarity outlined by Mohanty. One of the inspirations for Waiting For Men and for Traces initially derived from a book of photographs called African Canvas (1990) by Margaret Courtney-Clarke. The book includes photographs taken in the late 1980s in Oualata and Tiébélé, the locations of Ndiaye’s films.

Waiting For Men and Traces undermine the binary opposition of modernity versus tradition by drawing attention to the porous boundaries between a traditional artistic practice and centred female subjects who present themselves as contemporary African women, unafraid to both engage with and break from traditional values and practices. Traces features the young woman and single parent, Anetina, alongside her three grandmothers and her son. Anetina, the eldest child in her family, and the daughter of farmers, is unmarried and lives with her parents. She received part of her education in Pô (Burkina Faso) and sat her Baccalauréat there. Anetina takes an active interest in the artistic traditions and distinctive architecture that is typical of her village. She has a fluid conception of time that disrupts notions of past and present as separate and static entities; in one interview scene, Anetina stresses that being a single, unmarried woman (out of choice) of a certain age is a problem in her society. This moment precedes a self-assured shot of Anetina embracing her young son, followed by unnarrated shots of chalked and painted faces of figures depicted in the murals. Anetina’s personal experiences as a woman are interwoven with the pictorial history of her foremothers. We then return to the frontal shot of Anetina in the present, who goes on to address the struggles of being a woman in Tiébélé. She explains that women are expected to be submissive, to always concede, and they are never permitted to speak up. Her actions here simultaneously defy the strict expectations she is describing. This ‘to-camera’ interview scene fades into two reflective interlude shots of wall decorations, accompanied by jazz music, before a final dissolve takes us to an exquisite close-up of a cracked mirror positioned on the back wall inside a hair salon called La différence (‘Difference’) [27min 20].

Here we see the transition from the wall decoration to the cracked mirror in the hair salon where Anetina can be seen talking to the hairdresser and her client.

Anetina’s presence as a sentient subject is shown to be intimately interrelated with the material landscape, which contains physical traces of the intergenerational space of female creativity and artistic self-expression, which fuses the present with the past. Reflected in the cracked glass, we see Anetina positioned on the right-hand side, talking with the hairdresser and her client. The women’s bodies are splayed across the frame, fractured by the curved and diagonal cracks. This shot forms a further point of interrelationship between the figure of the woman and her creative work (represented here by the hairdresser braiding hair), and the disruptive splintering of her identity. The visual aesthetics appear to evoke the shattering of female experience and the need to find a different way forward to survive the gendered violence of patriarchal power. The mirror shot is accompanied by the distant voices of Anetina and the women in the salon, suggesting that if their image is fractured into isolated pieces, their collective sound continues. The camera cuts to a close-up of the hairdresser’s hands as she works, binding labour with creativity, and finishing with a shot of all three women waiting together outside the salon, positioned once again in the same (now un-fractured) space. The sequence ends, then, with a calm image of togetherness that transcends the idea of the broken or overpowered self. Anetina’s prior reflections on her life choices and possibilities, and on societal expectations, are brief and direct. The emphasis in Traces is not on the story and suffering of one singular woman, but on the community of women to which she belongs, including her differences from them and the common experiences that unite them.

In her introductory essay to the edited volume Making Face, Making Soul/Haciendo Caras (1990), Gloria Anzaldúa proposes the transgressive political act of ‘making faces’ as a metaphor for ‘constructing one’s identity’, for unbuilding and rebuilding.[v] The concept of the ‘interface’, which is at the centre of her essay, is defined as the space (the ‘inner face’) between the oppressive masks that have been imposed on women of colour throughout history. She refers to the craft of sewing to explain what she means by ‘interfacing’, namely, ‘sewing a piece of material between two pieces of fabric to provide support and stability to collar, cuff, yoke.’[vi] Anzaldúa describes the interface as something buried beneath ‘the masks we’ve internalized, one on top of another’, that have been brutally imposed by powerful others. The interface constitutes ‘the space from which we can thrust out and crack the masks’ to ‘become subjects in our own discourses.’ It is the ‘place’ between the masks where our diverse bodies can finally ‘intersect and interconnect’.[vii] The cracked mirror shot in Ndiaye’s film could certainly be interpreted as an image redolent of the splitting of female identity under patriarchy, echoing Anetina’s prior words, but it could also be interpreted as a shattering of the dualistic structures underpinning the workings of gendered power, which are replaced by the local intimacy of everyday interactions between women in the present, whose bodies are connected, through the motif of the hand, with the creative endeavours of the women who came before them. In a wider symbolic sense, this ‘broken’ image could be perceived as expressing the symbolic fracturing of gendered, racialised, and imperialistic power, in the sense of refusing reductive stereotypes of African women on screen, refusing the notion of ‘women’ as a homogeneous category, and disrupting the global dominance of white Euro-American media spaces that leave little room for other images, sounds, and stories.

In a workshop on ‘Decolonising African Cinema’, the Nigerian writer, filmmaker and photographer, Femi Odugbemi, discusses the obstacles preventing African stories from travelling globally. He highlights the decline of DVDs and the dominance of multibillion-dollar streaming platforms such as Netflix, calling for proper investment in spaces that preserve a connection between African stories and global audiences.[viii] Odugbemi also stresses the importance of educating young filmmakers and writers in the economics and politics of storytelling, especially the power relations underpinning funding and distribution processes. He states that from its early days, African cinema was not made for Africa or Africans, noting that sometimes even the cinematographer or the editor of seminal African films – the people responsible for creating the film’s audio-visual language – were French or British. African cinema ‘developed in a space where it was dependent financially’ on its colonial masters.[ix] He points out that film festivals in Francophone African countries are still, today, almost always funded by the ‘cultural arms’ of colonisers (white European-led organisations). Odugbemi suggests that vital questions to consider are: who are telling these stories and how are we educating those who tell them? By this, he is referring not only to issues of funding, distribution, and access, but also to the crucial idea that decolonisation also applies to the teaching of visual aesthetics and the politics of form. What is shown? How is it shown? And what is left out? As Ndiaye’s documentaries demonstrate so effectively, film is not only significant in terms of the event depicted, or for its linear representation of a historical moment. Social, political, and cultural transformation can take place with tremendous vigour via the expressive and affective potency of the organisation of sounds and images, including the way speech is arranged, the way bodies are positioned in space, and the way the spectator is interpellated into the imaginative space of cinema.

Reflecting, then, on my role as an academic and a teacher, and on the possibilities for decolonisation as a long-term process (not a reactionary gesture) in the university context, I find myself returning to Nikita Dhawan’s thoughts on the problematic mediating role of the postcolonial feminist who inevitably becomes a ‘representing intellectual’ for ‘marginalized’ voices in decolonising processes. This is not only a theoretical question but a practical one I must confront when communicating with Ndiaye about her films. Contemplating the conclusions to Gayatri Spivak’s 1988 essay ‘Can the Subaltern Speak?’, Dhawan suggests that part of the solution to the ‘double bind’ in which the postcolonial feminist finds herself, by participating in the structures she seeks to criticise, calls for ‘the persistent interrogation of one’s complicity in the re-colonization of “counter-spaces”’,[x] a doing applicable to the classroom, to publishing activities, to grant applications involving unpaid or underpaid collaborators, and also to collective events in the university, including those directly concerned with decolonisation.

Without having attended the screening of On a le temps pour nous in Brussels in 2019, and the post-screening Q&A with the director, which allowed Ndiaye and I to meet, and without Ndiaye’s receptiveness to my questions, and her commitment to the slow process of discussing her work (this has included me feeding back insights to my students for discussion, sending Ndiaye a sample of student coursework that discussed her films, and offering some feedback on film projects), my engagement with her films would not have been possible without being complicit, as Dhawan makes clear, in a re-colonising activity, no matter how compelling my scholarly analysis might be. Wider economic, industry-based, and educational contexts must be considered, and the relationship between filmmaker and scholar must be reciprocal and self-critical. Ndiaye’s careful questioning and challenging of my oversights, and those of the Western spectator, has enabled me to explore, with my students, the difficulty of teaching and studying such films without performing harmful recolonising gestures. These low-key, unstructured conversations have ultimately transformed our collaboration into an unpredictable and highly creative process that has exposed to me the necessity of listening to the silences between our conversations as much as to the words we have exchanged.

At a time when universities are urgently seeking to decolonise their curricular, to publicly display their commitment to decolonise, and to improve the ‘diversity’ of their student and staff bodies (a focus on ‘diversity’, for Anzaldúa, is just a means of sidestepping the difficult task of actually ‘dismantling Racism’),[xi] the process of conscious self-interrogation is one of the most immediately constructive actions I can take. Drawing on my own subjective experiences as a white (bisexual) woman in academia today, I think it is important that care is taken by those who already benefit from a wealth of opportunity, support, and visibility, not to project a wholesome image of (false) community and comfortable dissidence in the name of ‘solidarity’, simply to assuage the anxieties of those who continue to depend on, and reap the benefits of, their race, gender, sexuality, class, and able-bodied privileges. In disrupting very little at a grassroots level, this merely smooths over inconvenient differences and hides subtle injustices, and ultimately it strengthens the same white, Western, middle-class, heteronormative elite. Can the same faces, voices, hierarchies of knowledge, and centre-margin relations of power remain as they are if lasting change is to take place? What would happen if, instead of trying to create change around us in self-serving ways, we commit to the slow process of listening, in a non-defensive manner, to and with the discomfort of our own [trans]formation and we allow this to guide our actions and interactions?

Albertine Fox is Senior Lecturer in French Film at the University of Bristol. Her research explores the subversive potential of listening in experimental Francophone screen media. She is currently developing a book project on listening spaces and the face-to-face encounter in documentaries from the Francophone world. Other publications include articles on the Belgian filmmaker Chantal Akerman and an interview with the Lebanese filmmaker Corine Shawi. She is also the author of Godard and Sound: Acoustic Innovation in the Late Films of Jean-Luc Godard (I.B.Tauris/Bloomsbury, 2017).

Dr Albertine Fox, Senior Lecturer in French Film, Department of French, School of Modern Languages, University of Bristol

[i] Directors whose films have featured on the module as ‘set films’ (core teaching material) are: Alice Diop, Claire Simon, Amandine Gay, Chantal Akerman, Katy Léna Ndiaye, Corine Shawi, Agnès Varda, Jocelyne Saab, and Nada Mezni Hafaiedh.

[ii] Lindiwe Dovey, ‘On Teaching and Being Taught: Reflections on Decolonising Pedagogy’, PARSE, 11 (Summer 2020), pp. 1-22 (12). Online at: https://parsejournal.com/article/on-teaching-and-being-taught/ [accessed April 2020 and October 2021].

[iii] Chandra Talpade Mohanty, Feminism Without Borders: Decolonizing Theory, Practicing Solidarity (Durham:

Duke University Press, 2003), p. 39.

[iv] Ibid.

[v] Gloria Anzaldúa, ‘Haciendo caras, una entrada’, in Making Face, Making Soul/Haciendo Caras: Creative and Critical Perspectives by Feminists of Color (San Francisco: Aunt Lute Books, 1990), xv-xxviii (xvi).

[vi] Ibid., xv.

[vii] Ibid., xvi

[viii] Podcast: ‘Femi Odugbemi discusses Decolonising African Cinema’, Screen World (2020). Online at: https://screenworlds.org/publications/femi-odugbemi-discusses-decolonising-african-cinema/ [accessed June 2020 and May 2021].

[ix] Ibid.

[x] Nikita Dhawan, ‘Hegemonic Listening and Subversive Silences: Ethical-Political Imperatives’, in Alice Lagaay and Michael Lorber (ed.): Destruction in the Performative (Amsterdam/New York: Rodopi, 2012), pp. 47-60 (56).

[xi] Anzaldúa, ‘Haciendo caras, una entrada’, xxii.

More Essays